"Social organization"

"Social organization" tends to be all-encompassing

and a rather vague concept. Social organizations among primates vary primarily

on the basis of the following factors:

1. Group Size

2. Group Composition

3. Mating Systems

4. Social Roles - especially

for adult females and males

5. Various Types of Dominance

6. Permanence versus Instability

of Group Membership

7. Tendency to Aggregate into

Larger Social Groups

8. Presence of only Heterosexual

Reproductive Units, All-Male

Groups or All-Female Groups,

or Single Individuals

9. Patterns of Interactions.

The best way to examine primate

societies may be to divide them into groups based on: (A) large troops,

medium-size groups, and small units, or (B) multi-female and multi-male;

uni-male and multi-female; uni-male and uni-female, or (C) multiple mating

by males and females, polygynous, and monogamous.

Several trends can be noted if we

look at these possible ways to group primate societies. First, monogamous

groups are small, normally containing only one fully adult female and one

fully adult male and their offspring. Gibbons fit this model well. Second,

a system of multiple matings by both females and males or multi-females

are usually the largest of primate societies. Some groups can reach 300

individuals in these cases. Third, polygynous groups contain one adult

male and several adult females and off-spring and are moderate in size.

Gorilla troops fit this profile. Keep in mind that polygynous groups such

as this, also called harems, maximize reproduction by keeping a pool of

receptive females available. It is also true that the greatest sexual dimorphism

- difference in size between males and females - occur in polygynous societies.

Primates that live in monogamous

societies exhibit the following features: a lack of sexual dimorphism in

size and coloration; a lack of specialized defense roles against predators

by adult males; highly developed territoriality in both sexes; extensive

care of young by the adult male; and closely fashioned activities by adult

female and male.

Primates that live in polygymous

groups typically show the following characteristics: closely bonded  adult

females, somewhat peripheral or socially aloof reproductive male; strong

intolerance by the reproductive males of other, potentially reproductive

males; leadership shown by at least some females in many aspects of group

life, while the adult male shows an outward-from-the-group orientation;

some turnover in reproductive males.

adult

females, somewhat peripheral or socially aloof reproductive male; strong

intolerance by the reproductive males of other, potentially reproductive

males; leadership shown by at least some females in many aspects of group

life, while the adult male shows an outward-from-the-group orientation;

some turnover in reproductive males.

All primates are

social animals. They interact on a regular basis with each other. Most

tend to move, feed, and sleep in groups. The composition of these groups

differs from species to species. The following terms are used by primatologists

to characterize primate social groups: noyau, monogamous, polyandrous,

multimale, one-male, and fission-fusion societies.

The simplest social group found

among primates is the noyau. It is commonly found among noctural  primates

and is based on an individual female and her offspring. Adult males and

females do not form permanent mixed-sex groups nor do males and females

tend to travel with each other. Individual males have ranges that overlap

several different female ranges.

primates

and is based on an individual female and her offspring. Adult males and

females do not form permanent mixed-sex groups nor do males and females

tend to travel with each other. Individual males have ranges that overlap

several different female ranges.

The monogamous "family" consists

of one adult female, one male, and their offspring. Nonhuman primates that

are monogamous tend to mate for life and are usually highly territorial.

Gibbons and Indris are both typical of monogamous primates. In each case,

these species are highly vocal and use loud calls to warn others that they

"own" a territory.

The polyandrous groups consist of

a single reproducing female and several sexually active males. In these

groups, several of the males usually participate in the care of offspring.

Many primate species live in groups

consisting of a single adult male along with several females and their offspring. Adult males not living with females

form separate bands (all-male) or live alone as bachelors. The one-male

groups are almost invariably characterized by repeated efforts by outside

males to takeover the position of the resident male. In many instances,

dependent infants are killed as a result of a change in the status of a

resident male. Competition is high in the one-male society.

several females and their offspring. Adult males not living with females

form separate bands (all-male) or live alone as bachelors. The one-male

groups are almost invariably characterized by repeated efforts by outside

males to takeover the position of the resident male. In many instances,

dependent infants are killed as a result of a change in the status of a

resident male. Competition is high in the one-male society.

Another

type of social grouping among primates is the multimale group. Such groups

are characterized by complex intratroop politics and competition. These

groups tend to become relatively large in size with several males and numerous

females and offspring.

Another

type of social grouping among primates is the multimale group. Such groups

are characterized by complex intratroop politics and competition. These

groups tend to become relatively large in size with several males and numerous

females and offspring.

Among the Gombe Stream chimpanzees

that Jane Goodall has studied is still another form of primate society known as fission-fusion. The social group tends to separate (fission)

and then periodically join (fusion) for feeding in rich areas for example.

Individuals, females and their offspring, or temporary groups (harems,

all-male groups, for example) tend to form associations on a temporary

basis for various reasons. Yet, the group as a whole tends to reunite in

the ebb and flow of changing activities.

society known as fission-fusion. The social group tends to separate (fission)

and then periodically join (fusion) for feeding in rich areas for example.

Individuals, females and their offspring, or temporary groups (harems,

all-male groups, for example) tend to form associations on a temporary

basis for various reasons. Yet, the group as a whole tends to reunite in

the ebb and flow of changing activities.

Primate social groupings are

the result of many selective factors that influence the size, composition,

and dynamics of the group. It is the dynamics between individuals that

is of most importance to primate behavioral studies. One other aspect of

primate social behavior is important. Many studies demonstrate that the

social behavior for one species frequently changes with differences in

resource availability or even demographic fluxuations. This only reinforces

the idea that primate social groups are the product of selection. Therefore,

primate social groups have tended to evolve as a means for survival around

a variety of reproductive strategies. Advantages and disadvantages are

balanced through behavior responses that one finds in different primate

social groups.

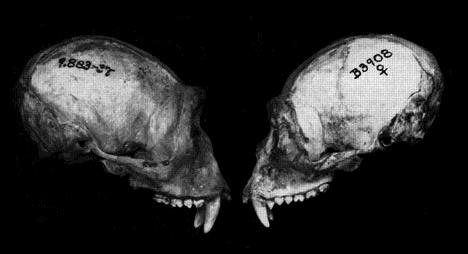

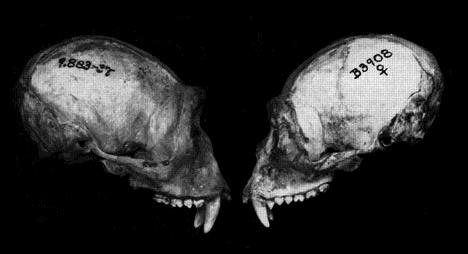

Sexual Dimorphism

and Size of Canines can be correlated to behaviors

relating to social organization. Sexual dimorphism is greatest and canines

large in polygynous societies. This tends also to be true in multi-male

and multi-female groups. Even in size is the rule for monogamous societies.

The following picture of a male and female gibbon skull show a remarkable

size similarity reflecting the lack of competition in a male-female bonding

behaviors among gibbons. The fossil record indicates that human sexual

dimorphism (the size differences between males and females) has decreased

over time but once was at a scale similar to gorillas where males are nearly

70% bigger than females.

Given

that gorillas tend to maximize care of infants and juveniles and estrus

biologically shuts down for a prolonged period in females, can you understand

why gorillas live in harems (polygymous socities)?

Given

that gorillas tend to maximize care of infants and juveniles and estrus

biologically shuts down for a prolonged period in females, can you understand

why gorillas live in harems (polygymous socities)?

Keep in mind that primate social

organization is varied. It is becoming clear that there are differences

between troops of chimpanzees or baboons. There are differences, for example,

that are striking between the chimpanzees that Jane Goodall has studied

in the Gombi area (as seen in the video People of the Forest) and a group

of chimpanzees known as Bonobo Chimpanzees (see reading on Bonobo Society

by Franz DeWaal.)

adult

females, somewhat peripheral or socially aloof reproductive male; strong

intolerance by the reproductive males of other, potentially reproductive

males; leadership shown by at least some females in many aspects of group

life, while the adult male shows an outward-from-the-group orientation;

some turnover in reproductive males.

adult

females, somewhat peripheral or socially aloof reproductive male; strong

intolerance by the reproductive males of other, potentially reproductive

males; leadership shown by at least some females in many aspects of group

life, while the adult male shows an outward-from-the-group orientation;

some turnover in reproductive males.

primates

and is based on an individual female and her offspring. Adult males and

females do not form permanent mixed-sex groups nor do males and females

tend to travel with each other. Individual males have ranges that overlap

several different female ranges.

primates

and is based on an individual female and her offspring. Adult males and

females do not form permanent mixed-sex groups nor do males and females

tend to travel with each other. Individual males have ranges that overlap

several different female ranges.

several females and their offspring. Adult males not living with females

form separate bands (all-male) or live alone as bachelors. The one-male

groups are almost invariably characterized by repeated efforts by outside

males to takeover the position of the resident male. In many instances,

dependent infants are killed as a result of a change in the status of a

resident male. Competition is high in the one-male society.

several females and their offspring. Adult males not living with females

form separate bands (all-male) or live alone as bachelors. The one-male

groups are almost invariably characterized by repeated efforts by outside

males to takeover the position of the resident male. In many instances,

dependent infants are killed as a result of a change in the status of a

resident male. Competition is high in the one-male society.

Another

type of social grouping among primates is the multimale group. Such groups

are characterized by complex intratroop politics and competition. These

groups tend to become relatively large in size with several males and numerous

females and offspring.

Another

type of social grouping among primates is the multimale group. Such groups

are characterized by complex intratroop politics and competition. These

groups tend to become relatively large in size with several males and numerous

females and offspring.

society known as fission-fusion. The social group tends to separate (fission)

and then periodically join (fusion) for feeding in rich areas for example.

Individuals, females and their offspring, or temporary groups (harems,

all-male groups, for example) tend to form associations on a temporary

basis for various reasons. Yet, the group as a whole tends to reunite in

the ebb and flow of changing activities.

society known as fission-fusion. The social group tends to separate (fission)

and then periodically join (fusion) for feeding in rich areas for example.

Individuals, females and their offspring, or temporary groups (harems,

all-male groups, for example) tend to form associations on a temporary

basis for various reasons. Yet, the group as a whole tends to reunite in

the ebb and flow of changing activities.

Given

that gorillas tend to maximize care of infants and juveniles and estrus

biologically shuts down for a prolonged period in females, can you understand

why gorillas live in harems (polygymous socities)?

Given

that gorillas tend to maximize care of infants and juveniles and estrus

biologically shuts down for a prolonged period in females, can you understand

why gorillas live in harems (polygymous socities)?